The complete history of JavaScript programming language

JavaScript / ECMAScript:

t all happened in six months from May to December 1995. Netscape Communications Corporation had a strong presence on the young web. Its browser, Netscape Communicator, was gaining traction as a competitor to NCSA Mosaic, the first popular web browser. Netscape was founded by the very same people that took part in the development of Mosaic during the early 90s, and now, with money and independence, they had the necessary freedom to seek further ways to expand the web. And that is precisely what gave birth to JavaScript.

Marc Andreessen, the founder of Netscape Communications and part of the ex-Mosaic team, had the vision that the web needed a way to become more dynamic. Animations, interaction, and other forms of small automation should be part of the web of the future. So the web needed a small scripting language that could interact with the DOM (which was not set in stone as it is right now). But, and this was an important strategic call at the time, this scripting language should not be oriented to big-shot developers and people with experience in the software engineering side of things. Java was on the rise as well, and Java applets were to be a reality soon. So the scripting language for the web would need to cater to a different type of audience: designers. Indeed, the web was static. HTML was still young and simple enough for non-developers to pick up. So whatever was to be part of the browser to make the web more dynamic should be accessible to non-programmers. And so the idea of Mocha was born. Mocha was to become a scripting language for the web. Simple, dynamic, and accessible to non-developers.

This is when Brendan Eich, father of JavaScript, came into the picture. Eich was contracted by Netscape Communications to develop a "Scheme for the browser". The scheme is a Lisp dialect and, as such, comes with very little syntactic weight. It is dynamic, powerful, and functional in nature. The web needed something of the sort: easy to grasp syntactically; dynamic, to reduce verbosity and speed up development; and powerful. Eich saw a chance to work on something he liked and joined forces.

At the moment there was a lot of pressure to come up with a working prototype as soon as possible. The Java language, née Oak at the time, was starting to get traction. Sun Microsystems was making a big push for it and Netscape Communications was about to close a deal with them to make Java available in the browser. So why Mocha (this was the early name for JavaScript)? Why create a whole new language when there was an alternative? The idea at the time was that Java was not suited for the type of audience that would consume Mocha: scripters, amateurs, designers. Java was just too big, too enterprises for the role. So the idea was to make Java available for big, professional, component writers; while Mocha would be used for small scripting tasks. In other words, Mocha was meant to be the scripting companion for Java, in a way analogous to the relationship between C/C++ and Visual Basic on the Windows platform.

At the moment this was all going on, engineers at Netscape started studying Java in detail. They went so far as starting to develop their own Java Virtual Machine. This VM, however, was quickly shot down on the grounds that it would never achieve perfect bug-for-bug compatibility with Sun's, a sound engineering call at the time.

There was a lot of internal pressure to pick one language as soon as possible. Python, Tcl, Scheme itself were all possible candidates. So Eich had to work fast. He had two advantages over the alternatives: freedom to pick the right set of features, and a direct line to those who made the calls. Unfortunately, he also had a big disadvantage: no time. Lots of important decisions had to be made and very little time was available to make them. JavaScript, a.k.a. Mocha, was born in this context. In a matter of weeks, a working prototype was functional, and so it was integrated into Netscape Communicator.

What was meant to be a Scheme for the browser turned into something very different? The pressure to close the deal with Sun and make Mocha a scripting companion to Java forced Eich's hand. A Java-like syntax was required, and familiar semantics for many common idioms was also adopted. So Mocha was not like Scheme at all. It looked like a dynamic Java, but underneath it was a very different beast: a premature lovechild of Scheme and Self, with Java looks.

The prototype of Mocha was integrated into Netscape Communicator in May 1995. In a short time, it was renamed LiveScript. At the moment, the word "live" was convenient from a marketing point of view. In December 1995, Netscape Communications and Sun closed the deal: Mocha/LiveScript would be renamed JavaScript, and it would be presented as a scripting language for small client-side tasks in the browser, while Java would be promoted as a bigger, professional tool to develop rich web components.

This first version of JavaScript set in stone many of the traits the language is known for today. In particular, its object-model, and its functional features were already present in this first version.

It is hard to say what would have happened had Eich failed to succeed in coming up with a working prototype in time. Working alternatives were not Java-like at all. Python, Tcl, Scheme, were very different. It would have been difficult for Sun to accept a companion language to Java that was so different, or that predated Java itself in history and development. On the other hand, Java was for a long time an important part of the web. Had Sun never been part of the equation, Netscape could have exercised more freedom at picking a language. This is true. But would Netscape have opted to adopt an external solution when an internally controlled and developed was possible? We will never know.

Different Implementations

When Sun and Netscape closed the deal to change the name of Mocha/LiveScript to JavaScript a big question was raised: what would happen to alternative implementations? Indeed, although Netscape was quickly becoming the preferred browser at the time, Internet Explorer was also being developed by Microsoft. From the very first days, JavaScript made such a considerable difference in user experience that competing browsers had no choice but to come up with a working solution, a working implementation of JavaScript. At the moment (and for a very long time), web standards were not strong. So Microsoft implemented their own version of JavaScript, called JScript. Keeping "Java" off the name avoided possible trademark issues. However, JScript was different in more than just name. Slight differences in implementation, in particular with regards to certain DOM functions, caused ripples that would still be felt many years into the future. JavaScript wars were fought on more fronts than just names and timelines and many of its quirks are just the wounds of these wars. The first version of JScript was included with Internet Explorer 3.0, released in August 1996.

Netscape's implementation of JavaScript also received an internal name. The version released with Netscape Navigator 2.0 was known as Mocha. In the fall of 1996, Eich rewrote most of Mocha into a cleaner implementation to pay off the technical debt caused by rushing it out of the door. This new version of Netscape's JavaScript engine was called SpiderMonkey. SpiderMonkey is still the name of the JavaScript engine found in Firefox, Netscape Navigator's grandson.

For several years, JScript and SpiderMonkey were the premier JavaScript engines. The features implemented by both, not always compatible, would define what would become of the web in the following years.

Major Design Features

Although JavaScript was born in a hurry, several powerful features were part of it from the beginning. These features would define JavaScript as a language and would allow it to outgrow its walled garden despite its quirks.

Whether any existing language could be used, instead of inventing a new one, was also not something I decided. The diktat from upper engineering management was that the language must “look like Java”. That ruled out Perl, Python, and Tcl, along with Scheme. Later, in 1996, John Ousterhout came by to pitch Tk and lament the missed opportunity for Tcl. I’m not proud, but I’m happy that I chose Scheme-ish first-class functions and Self-ish (albeit singular) prototypes as the main ingredients. The Java influences, especially y2k Date bugs but also the primitive vs. object distinction (e.g., string vs. String), were unfortunate. - Brendan Eich's blog: Popularity

Java-like Syntax

Although keeping the syntax close to Java was not the original idea behind JavaScript, marketing forces changed that. In retrospect, although a different syntax might have been more convenient for certain features, it is undeniable that a familiar syntax has helper JavaScript gain ground easily.

To this (modern) JavaScript example:

console.log('Hello world');

try {

const silo = new MissileSilo('silo.weapons.mil');

silo.launchMissile(process.argv[0]);

} catch(e) {

console.log('Unexpected exception' + e);

}Functions as First-Class Objects

In JavaScript, functions are simply one more object type. They can be passed around just like any other element. They can be bound to variables, and, in the later version of JavaScript, they can even be thrown as exceptions. This feature is a probable result of the strong influence Scheme had in JavaScript development.

var myFunction = function() {

console.log('hello');

}

otherFunction(myFunction);

myFunction.property = '1';By making function first-class objects, certain functional programming patterns are possible. For instance, later versions of JavaScript make use of certain functional patterns:

var a = [1, 2, 3];

a.forEach(function(e) {

console.log(e);

});These patterns have been exploited to great success by many libraries, such as underscore and immutable.js.

Prototype-based Object Model

Although the prototype-based object model was popularized by JavaScript, it was first introduced in the Self language. Eich had a strong preference for this model and it is powerful enough to model the more traditional approach of Simula-based languages such as Java or C++. In fact, classes, as implemented in the later version of JavaScript, are nothing more than syntactic sugar on top of the prototype system.

One of the design objectives of Self, the language that inspired JavaScript's prototypes, was to avoid the problems of Simula-style objects. In particular, the dichotomy between classes and instances was seen as the cause for many of the inherent problems in Simula's approach. It was argued that as classes provided a certain archetype for object instances, as the code evolved and grew bigger, it was harder and harder to adapt those base classes to unexpected new requirements. By making instances the archetypes from which new objects could be constructed, this limitation was to be removed. Thus the concept of prototypes: an instance that fills in the gaps of a new instance by providing its own behavior. If a prototype is deemed inappropriate for a new object, it can simply be cloned and modified without affecting all other child instances. This is arguably harder to do in a class-based approach (i.e. modify base classes).

function Vehicle(maxSpeed) {

this.maxSpeed = maxSpeed;

}

Vehicle.prototype.maxSpeed = function() {

return this.maxSpeed;

}

function Car(maxSpeed) {

Vehicle.call(this, maxSpeed);

}

Car.prototype = new Vehicle();The power of prototypes made JavaScript extremely flexible, sparking the development of many libraries with their own object models. A popular library called Stampit makes heavy use of the prototype system to extend and manipulate objects in ways that are not possible using a traditional class-based approach.

Prototypes have made JavaScript appear deceptively simple, empowering library authors.

A Big Quirk: Primitives vs Objects

Perhaps one of the biggest mistakes in the hurried development of JavaScript was making certain objects that behave similarly have different types. For instance, the type of a string literal ('HELLO WORLD') is not identical to the type of the STRING object This sometimes enforces unnecessary and confusing type checks.

> typeof "hello world"

< "string"

> typeof new String('hello world')

< "object"But this was just the start in JavaScript history. Its hurried development made certain design mistakes a possibility much too real. However, the advantages of having a language for the dynamic web could not be postponed, and history took over.

The rest is perverse, merciless history. JS beat Java on the client, rivaled only by Flash, which supports an offspring of JS, ActionScript. - Brendan Eich's blog: Popularity

A Trip Down Memory Lane: A Look at Netscape Navigator 2.0 and 3.0

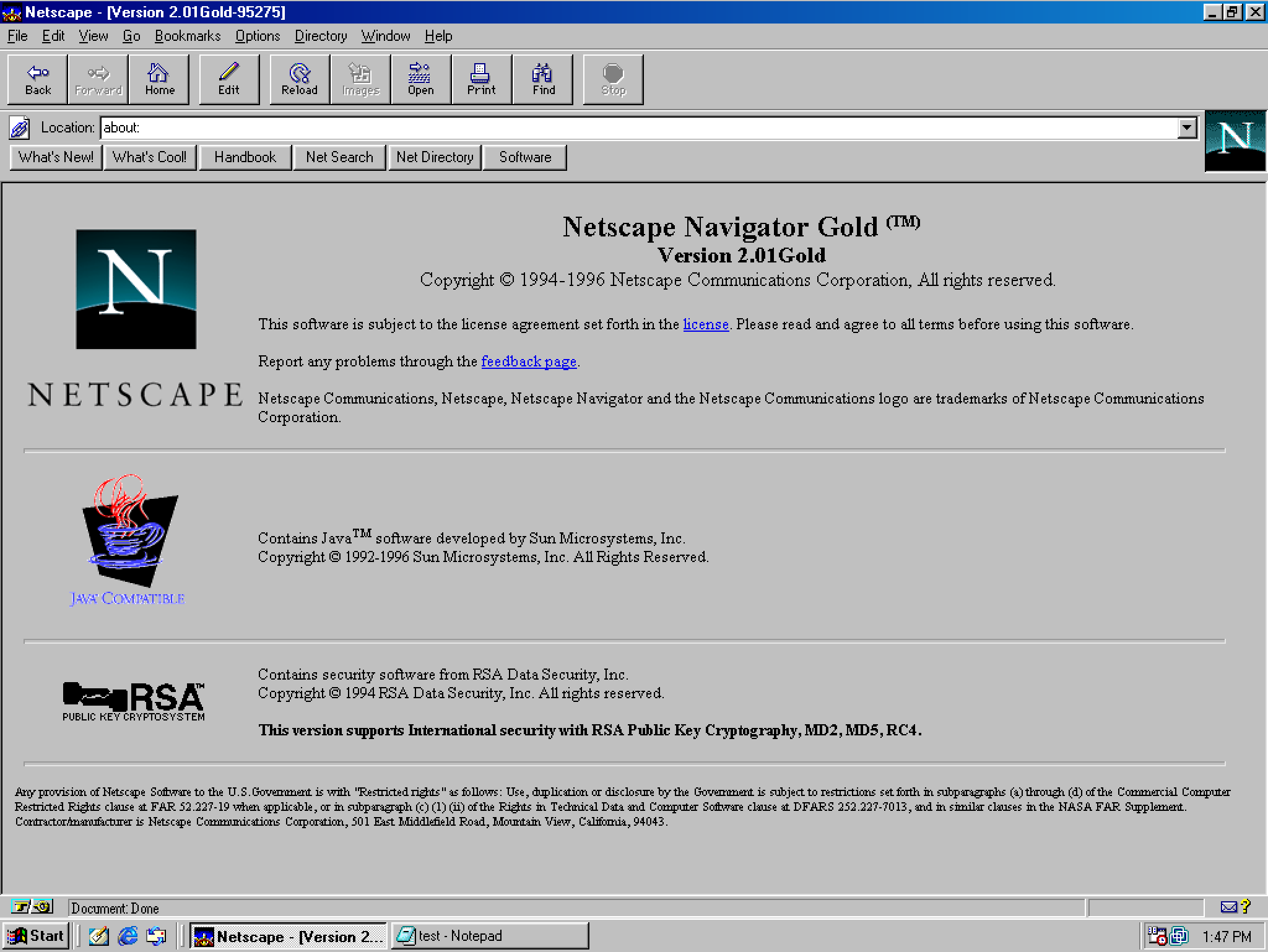

The first public release of JavaScript was integrated with Netscape Navigator 2.0, released in 1995. Thanks to the wonders of virtualization and abandonware websites, we can revive those moments today!

Unfortunately, many basic features of JavaScript were not working at the time. Anonymous functions and prototype chains, the two most powerful features were not working as they do today. Still, these features were already part of the design of the language and would be implemented correctly in the following years. It should be noted that the JavaScript interpreter in this release was considered in alpha state.

Fortunately, a year later, Netscape Navigator 3.0, released in 1996, was already making a big difference:

Note how the error gives us more information about what is going on. This lets us speculate the interpreter is specially treating the property. So we attempt to replace the object with a basic instance which we then modify. Et voilá, it works! Somewhat, at least. The assignment inside the function appears to do nothing. Clearly, there was a lot of work that needed to be done. Nonetheless, JavaScript in its state was usable for many tasks and its popularity continued growing.

Features such as regular expressions, JSON, and exceptions were still not available. JavaScript would evolve tremendously in the following years.

ECMAScript: JavaScript as a standard

The first big change for JavaScript after its public release came in the form of ECMA standardization. ECMA is an industry association formed in 1961 concerned solely with the standardization of information and communications systems.

Work on the standard for JavaScript was started in November 1996. The identification for the standard was ECMA-262 and the committee in charge was TC-39. By the time, JavaScript was already a popular element on many pages. This press release from 1996 puts the number of JavaScript pages at 300,000.

JavaScript and Java are cornerstone technologies of the Netscape ONE platform for developing Internet and Intranet applications. In the short time since their introduction last year, the new languages have seen rapid developer acceptance with more than 175,000 Java applets and more than 300,000 JavaScript-enabled pages on the Internet today according to www.hotbot.com. - Netscape Press Release

Standardization was an important step for such a young language, but a great call nonetheless. It opened up JavaScript to a wider audience and gave other potential implementors a voice in the evolution of the language. It also served the purpose of keeping other implementors in check. Back then, it was feared Microsoft or others would stray too far from the default implementation and cause fragmentation.

For trademark reasons, the ECMA committee was not able to use JavaScript as the name. The alternatives were not liked by many either, so after some discussion, it was decided that the language described by the standard would be called ECMAScript. Today, JavaScript is just the commercial name for ECMAScript.

ECMAScript 1 & 2: On The Road to Standardization

The first ECMAScript standard was based on the version of JavaScript released with Netscape Navigator 4 and still missed important features such as regular expressions, JSON, exceptions, and important methods for built-in objects. It was working much better in the browser, however. JavaScript was becoming better and better. Version 1 was released in June 1997.

Notice how our simple test of prototypes and functions now works correctly. A lot of work had gone under the hood in Netscape 4, and JavaScript benefited tremendously from it. Our example now essentially runs identically to any current browser. This is a great state to be for its first release as a standard.

The second version of the standard, ECMAScript 2, was released to fix inconsistencies between ECMA and the ISO standard for JavaScript (ISO/IEC 16262), so no changes to the language were part of it. It was released in June 1998.

An interesting quirk of this version of JavaScript is that errors that are not caught at compile time (which are in general left as unspecified) leave to the whim of the interpreter what to do about them. This is because exceptions were not part of the language yet.

ECMAScript 3: The First Big Changes

Work continued past ECMAScript 2 and the first big changes to the language saw the light. This version brought in:

- Regular expressions

- The do-while block

- Exceptions and the try/catch blocks

- More built-in functions for strings and arrays

- Formatting for numeric output

- The in and instanceof operators

- Much better error handling

ECMAScript 3 was released in December 1999.

This version of ECMAScript spread far and wide. It was supported by all major browsers at the time and continued to be supported many years later. Even today, some transpilers can target this version of ECMAScript when producing output. This made ECMAScript 3 the baseline target for many libraries, even when later versions of the standard were released.

Although JavaScript was more in use than ever, it was still primarily a client-side language. Many of its new features brought it closer to breaking out of that cage.

Netscape Navigator 6, released in November 2000 and a major change from past versions, supported ECMAScript 3. Almost a year and a half later, Firefox, a lean browser based on the codebase for Netscape Navigator, was released supporting ECMAScript 3 as well. These browsers, alongside Internet Explorer, continued pushing JavaScript growth.

The birth of AJAX

AJAX, asynchronous JavaScript, and XML was a technique that was born in the years of ECMAScript 3. Although it was not part of the standard, Microsoft implemented certain extensions to JavaScript for its Internet Explorer 5 browser. One of them was the XMLHttpRequest function (in the form of the XMLHTTP ActiveX control). This function allowed a browser to perform an asynchronous HTTP request against a server, thus allowing pages to be updated on the fly. Although the term AJAX was not coined until years later, this technique was pretty much in place.

The term AJAX was coined by Jesse James Garrett, co-founder of Adaptive Path, in this iconic blog post.

XMLHttpRequest proved to be a success and years later was integrated into its separate standard (as part of the WHATWG and the W3C groups).

This evolution of features, an implementor bringing something interesting to the language and implementing it in its browser, is still the way JavaScript and associated web standards such as HTML and CSS continue to evolve. At the time, however, there was much less communication between parties, which resulted in delays and fragmentation. To be fair, JavaScript development today is much more organized, with procedures for presenting proposals by any interested parties.

Playing with Netscape Navigator 6

This release supports exceptions, the main showstopper previous versions suffered when trying to access Google. Incredibly, trying to access Google in this version results in a viewable, working page, even today. In contrast, we attempted to access Google using Netscape Navigator 4, and we got hit by the lack of exceptions, incomplete rendering, and bad layout. Things were moving fast for the web, even back then.

Playing with Internet Explorer 5

Internet Explorer 5 was capable of rendering the current version of Google as well. It is well known, however, there were many differences in the implementation of certain features between Internet Explorer and other browsers. These differences plagued the web for many years and were the source of frustration for web developers for a long time, who usually had to implement special cases for Internet Explorer users.

In fact, to access the XMLHttpRequest object in Internet Explorer 5 and 6, it was necessary to resort to ActiveX. Other browsers implemented it as a native object.

var xhr = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");Arguably, it was Internet Explorer 5 who brought the idea to the table first. It was not until version 7 that Microsoft started to follow standards and consensus more closely. Some outdated corporate sites still require old versions of Internet Explorer to run correctly.

ECMAScript 3.1 and 4: The Years of Struggle

Unfortunately, the following years were not good for JavaScript development. As soon as work on ECMAScript 4 started, strong differences in the committee started to appear. There was a group of people that thought JavaScript needed features to become a stronger language for large-scale application development. This group proposed many features that were big in scope and in changes. Others thought this was not the appropriate course for JavaScript. The lack of consensus, and the complexity of some of the proposed features, pushed the release of ECMAScript 4 further and further away.

Work on ECMAScript 4 had begun as soon as version 3 came out the door in 1999. Many interesting features were discussed internally at Netscape. However, interest in implementing them had dwindled and work on a new version of ECMAScript stopped after a while in the year 2003. An interim report was released and some implementors, such as Adobe (ActionScript) and Microsoft (JScript.NET), used it as the basis for their engines. In 2005, the impact of AJAX and XMLHttpRequest sparked again the interest in a new version of JavaScript and TC-39 resumed work. Years passed and the set of features grew bigger and bigger. At the peak of development, ECMAScript 4 had features such as:

- Classes

- Interfaces

- Namespaces

- Packages

- Optional type annotations

- Optional static type checking

- Structural types

- Type definitions

- Multi methods

- Parameterized types

- Proper tail calls

- Iterators

- Generators

- Introspection

- Type discriminating exception handlers

- Constant bindings

- Proper block scoping

- Destructuring

- Succinct function expressions

- Array comprehensions

The ECMAScript 4 draft describes this new version as intended for programming in the large. If you are already familiar with ECMAScript 6/2015 you will notice that many features from ECMAScript 4 were reintroduced in it.

Though flexible and formally powerful, the abstraction facilities of ES3 are often inadequate in practice for the development of large software systems. ECMAScript programs are becoming larger and more complex with the adoption of Ajax programming on the web and the extensive use of ECMAScript as an extension and scripting language in applications. The development of large programs can benefit substantially from facilities like static type checking, name hiding, early binding and other optimization hooks, and direct support for object-oriented programming, all of which are absent from ES3. - ECMAScript 4 draft

An interesting piece of history is the following Google Docs spreadsheet, which displays the state of implementation of several JavaScript engines and the discussion of the parties involved in that.

The committee that was developing ECMAScript 4 was formed by Adobe, Mozilla, Opera (in an unofficial capacity), and Microsoft. Yahoo entered the game as most of the standards and features were already decided. Doug Crockford, an influential JavaScript developer, was the person sent by Yahoo for this. He voiced his concerns in strong opposition to many of the changes proposed for ECMAScript 4. He got strong support from the Microsoft representative. In the words of Crockford himself:

But it turned out that the Microsoft member had similar concerns — he also thought the language was getting too big and was out of control. He had not said anything prior to my joining the group because he was concerned that, if Microsoft tried to get in the way of this thing, it would be accused of anti-competitive behavior. Based on Microsoft's past performance, there were maybe some good reasons for them to be concerned about that — and it turned out, those concerns were well-founded, because that happened. But I convinced him that Microsoft should do the right thing, and to his credit, he decided that he should, and was able to convince Microsoft that it should. So Microsoft changed their position on ES4. - Douglas Crockford — The State and Future of JavaScript

What started as doubts, soon became a strong stance against JavaScript. Microsoft refused to accept any part of ECMAScript 4 and was ready to take every necessary action to stop the standard from getting approved (even legal actions). Fortunately, people in the committee managed to prevent a legal struggle. However, the lack of consensus effectively prevented ECMAScript 4 from advancing.

Some of the people at Microsoft wanted to play hardball on this thing, they wanted to start setting up paper trails, beginning grievance procedures, wanting to do these extra legal things. I didn't want any part of that. My disagreement with ES4 was strictly technical and I wanted to keep it strictly technical; I didn't want to make it nastier than it had to be. I just wanted to try to figure out what the right thing to do was, so I managed to moderate it a little bit. But Microsoft still took an extreme position, saying that they refused to accept any part of ES4. So the thing got polarized, but I think it was polarized as a consequence of the ES4 team refusing to consider any other opinions. At that moment the committee was not in consensus, which was a bad thing because a standards group needs to be in consensus. A standard should not be controversial. - Douglas Crockford — The State and Future of JavaScript

Crockford pushed forward the idea of coming up with a simpler, reduced set of features for the new standard, something all could agree on: no new syntax, only practical improvements born out of the experience of using the language. This proposal came to be known as ECMAScript 3.1.

For a time, both standards coexisted, and two informal committees were set in place. ECMAScript 4, however, was too complex to be finished in the face of discordance. ECMAScript 3.1 was much simpler, and, despite the struggle at ECMA, was completed.

The end for ECMAScript 4 came in the year 2008 when Eich sent an email with the executive summary of a meeting in Oslo which detailed the way forward for ECMAScript and the future of versions 3.1 and 4.

The conclusions from that meeting were to:

- Focus work on ES3.1 with the full collaboration of all parties, and target two interoperable implementations by early next year.

- Collaborate on the next step beyond ES3.1, which will include syntactic extensions but which will be more modest than ES4 in both semantic and syntactic innovation.

- Some ES4 proposals have been deemed unsound for the Web, and are off the table for good: packages, namespaces, and early binding. This conclusion is key to Harmony.

- Other goals and ideas from ES4 are being rephrased to keep consensus in the committee; these include a notion of classes based on existing ES3 concepts combined with proposed ES3.1 extensions.

All in all, ECMAScript 4 took almost 8 years of development and was finally scrapped. A hard lesson for all who were involved.

The word "Harmony" appears in the conclusions above. This was the name of the project for future extensions for JavaScript received. Harmony would be the alternative that everyone could agree on. After the release of ECMAScript 3.1 (in the form of version 5, as we'll see below), ECMAScript Harmony became the place where all new ideas for JavaScript would be discussed.

ActionScript

ActionScript was a programming language based on an early draft for ECMAScript 4. Adobe implemented it as part of its Flash suite of applications and was the sole scripting language supported by it. This made Adobe take a strong stance in favor of ECMAScript 4, even going as far as releasing their engine as open-source (Tamarin) in hopes of speeding ECMAScript 4 adoption. An interesting take on the matter was exposed by Mike Chambers, an Adobe employee:

ActionScript 3 is not going away, and we are not removing anything from it based on the recent decisions. We will continue to track the ECMAScript specifications, but as we always have, we will innovate and push the web forward when possible (just as we have done in the past). - Mike Chamber's blog

It was the hope of ActionScript developers that innovation in ActionScript would drive features in ECMAScript. Unfortunately, this was never the case, and what later came to ECMAScript 2015 was in many ways incompatible with ActionScript.

Some saw this move as an attempt by Microsoft to remain in control of the language and the implementation. The only viable engine for ECMAScript 4 at the moment was Tamarin, so Microsoft, who had 80% browser market share at the moment, could continue using its own engine (and extensions) without paying the cost of switching to a competitor's alternative or taking time to implement everything in-house. Others simply say Microsoft's objections were merely technical, like those from Yahoo. Microsoft's engine, JScript, at this point had many differences with other implementations. Some have seen this as a way to remain covertly in control of the language.

ActionScript remains today the language for Flash, which, with the advent of HTML5 has slowly faded in popularity.

ActionScript remains the closest look to what ECMAScript 4 could have been if it had been implemented by popular JavaScript engines:

E4X? What is E4X?

E4X was the name an extension for ECMAScript received. It was released during the years of ECMAScript 4 development (2004), so the moniker E4X was adopted. Its actual name is ECMAScript for XML and was standardized as ECMA-357. E4X extends ECMAScript to support native processing and parsing of XML content. XML is treated as a native data type in E4X. It saw initial adoption by major JavaScript engines, such as SpiderMonkey, but it was later dropped due to lack of use. It was removed from Firefox in version 21.

Other than the number "4" in its name, E4X has little to do with ECMAScript 4.

A sample of what E4X used to bring to the table:

var sales = <sales vendor="John">

<item type="peas" price="4" quantity="6"/>

<item type="carrot" price="3" quantity="10"/>

<item type="chips" price="5" quantity="3"/>

</sales>;

alert( sales.item.(@type == "carrot").@quantity );

alert( sales.@vendor );

for each( var price in sales..@price ) {

alert( price );

}

delete sales.item[0];

sales.item += <item type="oranges" price="4"/>;

sales.item.(@type == "oranges").@quantity = 4;Arguably, other data formats (such as JSON) have gained wider acceptance in the JavaScript community, so E4X came and went without much ado.

ECMAScript 5: The Rebirth Of JavaScript

After the long struggle of ECMAScript 4, from 2008 onwards, the community focused on ECMAScript 3.1. ECMAScript 4 was scrapped. In the year 2009 ECMAScript 3.1 was completed and signed-off by all involved parties. ECMAScript 4 was already recognized as a specific variant of ECMAScript even without any proper release, so the committee decided to rename ECMAScript 3.1 to ECMAScript 5 to avoid confusion.

ECMAScript 5 became one of the most supported versions of JavaScript, and also became the compiling target of many transpilers. ECMAScript 5 was wholly supported by Firefox 4 (2011), Chrome 19 (2012), Safari 6 (2012), Opera 12.10 (2012), and Internet Explorer 10 (2012).

ECMAScript 5 was a rather modest update to ECMAScript 3, it included:

ECMAScript 5 saw another iteration in the year 2011 in the form of ECMAScript 5.1. This release clarified some ambiguous points in the standard but didn't provide any new features. All new features were slated for the next big release of ECMAScript.

ECMAScript 6 (2015) & 7 (2016): a General Purpose Language

The ECMAScript Harmony proposal became a hub for future improvements to JavaScript. Many ideas from ECMAScript 4 were canceled for good, but others were rehashed with a new mindset. ECMAScript 6, later renamed ECMAScript 2015, was slated to bring big changes. Almost every change that required syntactic changes was pushed back to this version. This time, however, the committee achieved unity and ECMAScript 6 was finally released in the year 2015. Many browser vendors were already working on implementing its features, but with a big changelog, things took some time. Even today, not all browsers have complete coverage of ECMAScript 2015 (although they are very close).

The release of ECMAScript 2015 caused a big jump in the use of transpilers such as Babel or Traceur. Even before the release, as these transpilers tracked the progress of the technical committee, people were already experiencing many of the benefits of ECMAScript 2015.

Some of the big features of ECMAScript 4 were implemented in this version of ECMAScript. However, they were implemented with a different mindset. For instance, classes in ECMAScript 2015 are little more than syntactic sugar on top of prototypes. This mindset eases the transition and the development of new features.

We did an extensive overview of the new features of ECMAScript 2015 in our A Rundown of JavaScript 2015 features article. You can also take a look at the ECMAScript compatibility table to get a sense of where we stand right now in terms of implementation.

A short summary of the new features follows:

- Let (lexical) and const (unreadable) bindings

- Arrow functions (shorter anonymous functions) and lexical this (enclosing scope this)

- Classes (syntactic sugar on top of prototypes)

- Object literal improvements (computed keys, shorter method definitions, etc.)

- Template strings

- Promises

- Generators, tables, iterators, and for..of

- Default arguments for functions and the rest operator

- Spread syntax

- Destructuring

- Module syntax

- New collections (Set, Map, WeakSet, WeakMap)

- Proxies and Reflection

- Symbols

- Typed arrays

- Support for subclassing built-ins

- Guaranteed tail-call optimization

- Simpler Unicode support

- Binary and octal literals

Classes, let const, promises, generators, iterators, modules, etc. These are all features meant to take JavaScript to a bigger audience and to aid in programming at large.

It may come as a surprise that so many features could get past the standardization process when ECMAScript 4 failed. In this sense, it is important to remark that many of the most invasive features of ECMAScript 4 were not reconsidered (namespaces, optional typing), while others were rethought in a way they could get past previous objections (making classes syntactic sugar on top of prototypes). Still, ECMAScript 2015 was the hard word and took almost 6 years to complete (and more to fully implement). However, the fact that such an arduous task could be completed by the ECMAScript technical committee was seen as a good sign of things to come.

A small revision to ECMAScript was released in the year 2016. This small revision was the consequence of a new release process implemented by TC-39. All new proposals must go through a four-stage process. Every proposal that reaches stage 4 has a strong chance of getting included in the next version of ECMAScript (though the committee may still opt to push back its inclusion). This way proposals are developed almost on their own (though interaction with other proposals must be taken into account). Proposals do not stop the development of ECMAScript. If a proposal is ready for inclusion, and enough proposals have reached stage 4, a new ECMAScript version can be released.

The version released in the year 2016 was a rather small one. It included:- The exponentiation operator (**)

- A few minor corrections (generators can't be used with new, etc.)

However, certain interesting proposals have already reached stage 4 in 2016, so what lies ahead for ECMAScript?

The Future and Beyond: ECMAScript 2017 and later

Other stages 4 proposals are minor in scope:

These proposals are all slated for release in the year 2017, however, the committee may choose to push them back at their discretion. Just having async/await would be an exciting change, however.

But the future does not end there! We can take a look at some of the other proposals to get a sense of what lies further ahead. Some interesting ones are:

- SIMD APIs

- Asynchronous iteration (async/await + iteration)

- Generator arrow functions

- 64-bit integer operations

- Realms (state separation/isolation)

- Shared memory and atomics

JavaScript is looking more and more like a general-purpose language. But there is one more big thing in JavaScript's future that will make a big difference.

If you have not heard about WebAssembly, you should read about it. The explosion of libraries, frameworks and general development that was sparked since ECMAScript 5 was released has made JavaScript an interesting target for other languages. For big codebases, interoperability is key. Take games for instance. The lingua-franca for game development is still C++, and it is portable to many architectures. Porting a Windows or console game to the browser was seen as an insurmountable task. However, the incredible performance of current JIT JavaScript virtual machines made this possible. Thus things like Emscripten, an LLVM-to-JavaScript compiler, were born.

Mozilla saw this and started working on making JavaScript a suitable target for compilers. Asm.js was born. Asm.js is a strict subset of JavaScript that is ideal as a target for compilers. JavaScript virtual machines can be optimized to recognize this subset and produce even better code than is currently possible in normal JavaScript code. The browser is slowly becoming a whole new target for compiling apps, and JavaScript is at the center of it.

However, there are certain limitations that not even Asm.js can resolve. It would be necessary to make changes to JavaScript that have nothing to do with its purpose. To make the web a proper target for other languages something different is needed, and that is exactly what WebAssembly is. WebAssembly is a bytecode for the web. Any program with a suitable compiler can be compiled to WebAssembly and run on a suitable virtual machine (JavaScript virtual machines can provide the necessary semantics). In fact, the first versions of WebAssembly aim at 1-on-1 compatibility with the Asm.js specification. WebAssembly not only brings the promise of faster load times (bytecode can be parsed faster than text) but possible optimizations not available at the moment in Asm.js. Imagine a web of perfect interoperability between JavaScript and your existing code.

At first sight, this might appear to compromise the growth of JavaScript, but in fact, it is quite the contrary. By making it easier for other languages and frameworks to be interoperable with JavaScript, JavaScript can continue its growth as a general-purpose language. And WebAssembly is the necessary tool for that.

At the moment, development versions of Chrome, Firefox, and Microsoft Edge support a draft of the WebAssembly specification and are capable of running demo apps.

Aside: JavaScript use at Auth0

At Auth0 we are heavy users of JavaScript. From our Lock library to our backend, JavaScript powers the core of our operations. We find its asynchronous nature and the low entry barrier for new developers essential to our success. We are eager to see where the language is headed and the impact it will have on its ecosystem.

Sign up for a free Auth0 account

and take a first-hand look at a production-ready ecosystem written in JavaScript. And don't worry, we have client libraries for all popular frameworks and platforms!

Auth0 offers a generous free tier to get started with modern authentication.

Recently, we have released a product called Auth0 Extend. This product enables companies to provide to their customers an easy-to-use extension point that accepts JavaScript code. With Auth0 Extend, customers can create custom business rules, scheduled jobs, or connect to the ecosystem by integrating with other SaaS systems, like Marketo, Salesforce, and Concur. All using plain JavaScript and NPM modules.

Conclusion

The history of JavaScript has been long and full of bumps. It was proposed as a "Scheme for the web". Early on it got Java-like syntax strapped on. Its first prototype was developed in a matter of weeks. It suffered the perils of marketing and got three names in less than two years. It was then standardized and got a name that sounded like a skin disease. After three successful releases, the fourth got caught up in development hell for almost 8 years. Fingers got pointed around. Then, by the sheer success of a single feature (AJAX), the community got its act back together and development was resumed. Version 4 was scrapped and a minor revision, known by everyone as version 3.1, got renamed to version 5. Version 6 spent many years in development (again) but this time the committee succeeded, but nonetheless decided to change the name again, this time to 2015. This revision was big and took a lot of time to get implemented. But finally, new air was breathed into JavaScript. The community is as active as ever. Node.js, V8, and other projects have brought JavaScript to places it was never thought for. Asm.js, WebAssembly is about to take it even further. And the active proposals in different stages are all making JavaScript's future as bright as ever. It's been a long road, full of bumps, and JavaScript is still one of the most successful languages ever. That's a testament in itself. Always bet on JavaScript.

"JavaScript is still one of the most successful languages ever, always bet on JavaScript"

Post a Comment